Frozen Embryo Transfer: Timelines, Success Rates, and How to Prepare

Medically reviewed by Linda Streety, RN, BSN

What is a frozen embryo transfer?

During in-vitro fertilization (IVF), your clinician may choose to conduct either a fresh embryo transfer or a frozen embryo transfer (FET). During FET, a cryopreserved embryo (or embryos) is thawed and placed inside the uterus.

Six Second Snapshot

-

Your doctor will either coordinate the FET procedure with your natural ovulation cycle, or schedule FET to coordinate with medications that control your ovulation and help to optimize your uterine lining.

-

You will have either a natural FET, supplemented natural FET, or medicated FET, depending on the medications you need to support embryo implantation and early pregnancy.

-

Since cryopreservation technology has improved in recent years and FET allows for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) on the embryos, FET has become the preferred method for many people.

How long after egg retrieval does frozen embryo transfer occur?

To allow your body to recover from egg retrieval, your clinician will likely have you wait at least one full menstrual cycle – about 6-8 weeks after your egg retrieval – before a frozen embryo transfer. That said, you can choose to wait months or even years after egg retrieval to have an embryo transfer!

While a frozen embryo transfer offers more flexibility than a fresh embryo transfer, it still must be timed to coincide with ovulation. Your doctor will either plan the FET procedure to occur in coordination with your natural ovulation cycle, or it can be coordinated with medications that control your ovulation and help to optimize your uterine lining.

If you are concerned about genetic or chromosomal abnormalities which can increase your chance of miscarriage or cause lifelong disability for your child, you may opt to do preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) on your embryos. If you decide to do PGT, you will wait until your PGT results are in before having a frozen embryo transfer.

Frozen Embryo Transfer Timelines

The reason FET occurs just after ovulation is because that’s when your uterine lining is primed to support a pregnancy. Depending on your particular hormones, your clinician will suggest either a natural FET or a medicated one, in which hormone medications help to prepare and coordinate your body’s readiness for pregnancy.

Below are descriptions of types of frozen embryo transfer cycles and sample cycle calendars.

Natural Frozen Transfer

During a natural FET, your clinician will time your embryo transfer to coordinate with when you naturally ovulate. This is because your uterine lining will be primed to accept an embryo at this point in your menstrual cycle. If you are producing progesterone on your own, you can opt for a natural FET.

Supplemented Natural Frozen Transfer

Though this transfer schedule aligns with your natural cycle, your clinician may supplement this process with hormones. While FET still coordinates with your natural ovulation timing, an hCG shot can ensure that ovulation occurs, and supplemental progesterone can help your body support an early pregnancy.

Medicated Frozen Transfer

In a medicated (or “programmed”) transfer, your clinician will prescribe estrogen and progesterone medications (and sometimes gonadotropin-releasing hormone, or GnRH) to optimize your uterine lining for pregnancy. This is important if your body is not producing progesterone on its own. You may begin medication before embryo transfer and continue for weeks afterward. A medicated frozen transfer may also include an endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA), a diagnostic test involving a biopsy of the endometrium to determine the optimal date to conduct the embryo transfer.

A medicated frozen transfer cycle may begin with daily birth control pills starting one month before the menstrual cycle during which the embryo transfer will occur. It may also include Lupron (GnRH agonist) supplementation from 7-10 days before the menstrual cycle begins to day 16 of the cycle.

What are the frozen embryo transfer success rates?

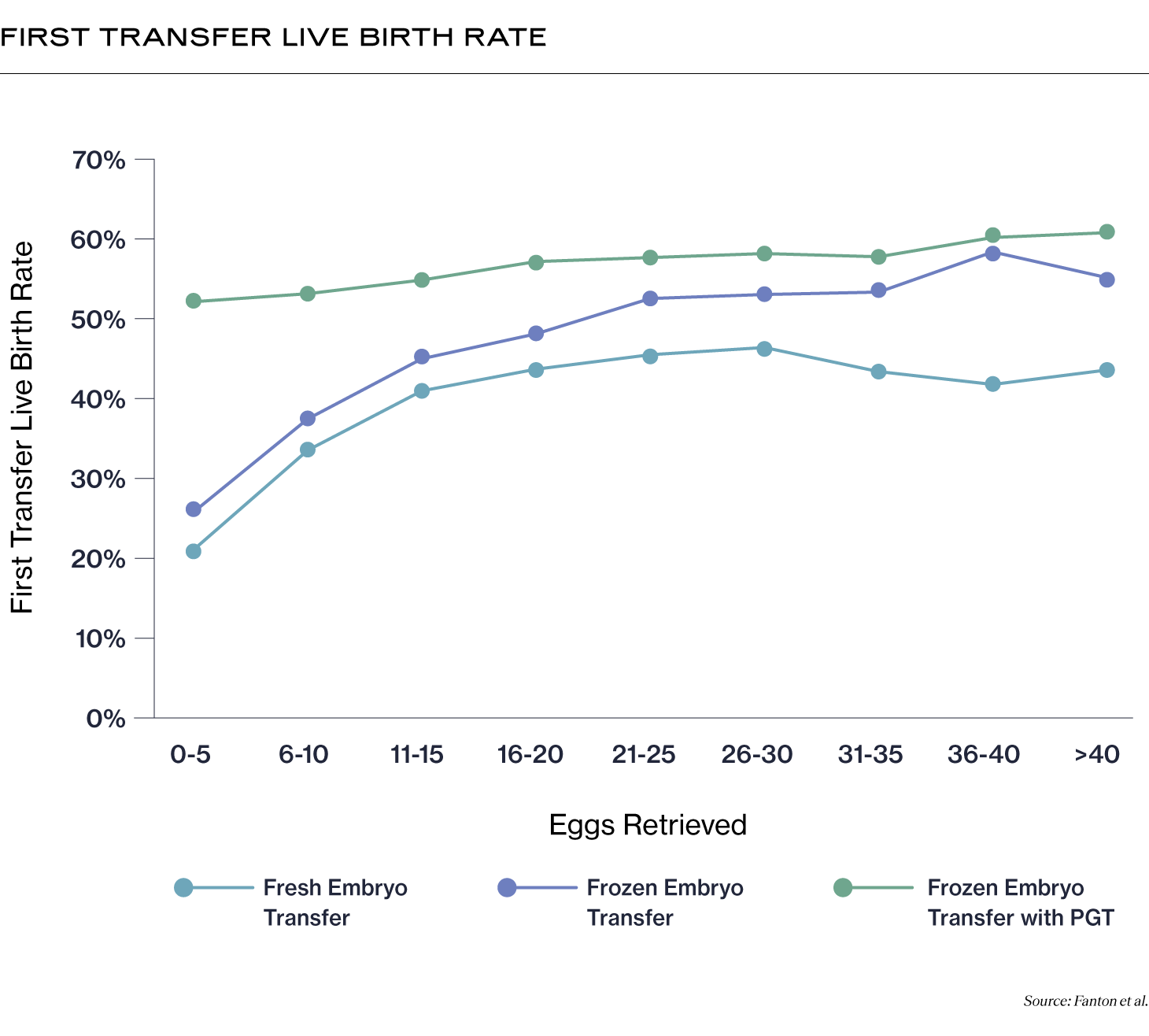

Frozen embryo transfer success rates are determined by the age of the person providing the eggs at the time of egg retrieval; your age at embryo transfer is less important to your chance of success. Below is the cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) for primary transfer for freeze-all IVF cycles, by maternal age at the time of egg retrieval:

Since cryopreservation technology has improved in recent years, FET has become the preferred method for many people because it means:

- Your body can recover after ovarian stimulation

- You can freeze extra embryos produced from IVF that can be transferred later

- You can decide when you want to start trying to get pregnant

- You can opt for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) on the embryos, which may reduce the number of transfers needed before pregnancy

Which is right for you: fresh or frozen transfer?

Your reproductive endocrinologist will consider a number of factors in deciding whether you should do a fresh or frozen embryo transfer, including:

Your risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)

OHSS is a potentially dangerous condition that can develop after ovarian stimulation. During OHSS, the ovaries swell and leak fluid into the body. Freezing embryos rather than doing a fresh transfer can significantly reduce the risk of OHSS (1). However, this has to be weighed against an increase in risk of pre-eclampsia with frozen embryo transfer.

Whether you plan to do PGT testing

If you do opt for PGT, research published by Alife researchers in Fertility and Sterility in 2023 shows that primary transfer success rates for frozen transfer with PGT are higher than for frozen transfer without PGT or fresh transfer (2). It’s important to note that frozen transfer success rates could be higher than with fresh transfer due to elevated estradiol levels during fresh transfers, or because fresh transfers are more common for lower prognosis patients.

Your age at the time of egg retrieval

This may also affect your RE’s decision. A retrospective study published in Fertility and Sterility found that while the pregnancy rates were about the same for patients under 35, freeze-only cycles were more likely to result in pregnancy for patients over 35 (3).

It’s important to note that not all ovarian stimulation cycles result in a viable embryo, and embryo transfer does not necessarily lead to a live birth. Needing multiple transfers is common, especially for older patients (4), and it’s helpful to factor that into your expectations for IVF.

How to prepare for your frozen embryo transfer

There are several steps you can take to increase your chance of success before a frozen embryo transfer.

Consistently take your medications

If your clinician has prescribed hormone medications before your frozen embryo transfer, it’s important to administer them every day that they’re prescribed. If you were prescribed progesterone injections – which are administered intramuscularly – and are having difficulty tolerating them, you can talk to your doctor about the progesterone vaginal gel Crinone, which has been shown to be as effective as the shots (5).

Take a prenatal vitamin

If you aren’t already taking a prenatal vitamin, start taking one 30 days before embryo transfer to help prevent birth defects during early pregnancy.

Get plenty of sleep

According to a study published in Fertility and Sterility in 2023, patients with good sleep quality had a higher live birth rate (50.5%) after embryo transfer than patients with poor sleep quality (45.7%) (6).

Take steps to optimize your uterine lining

Supplementing with sufficient Vitamin E and L-Arginine before embryo transfer can help to ensure your uterine lining is ready for implantation.

Acupuncture

There’s some evidence that acupuncture can help with embryo transfer success rates (7).

While some sources say that caffeine may affect your chance of success with IVF, a 2019 study found that caffeine intake did not affect IVF outcomes (8). Similarly, low to moderate alcohol intake before embryo transfer also did not seem to affect outcomes (9).

After embryo transfer, you should continue to take any medications prescribed to you as well as your prenatal vitamin, and get plenty of rest! If you take NSAIDS, talk to your clinician about whether you should continue taking them and if there is an alternative for your pain. NSAIDS have been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage in early pregnancy (10). You should also begin to abstain from alcohol and caffeine.

Recent Articles

References

-

Roque, Matheus, et al. “Fresh versus Elective Frozen Embryo Transfer in IVF/ICSI Cycles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Reproductive Outcomes.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 25, no. 1, 2019, pp. 2–14, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30388233, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmy033.

-

Fanton, Michael, et al. “A Higher Number of Oocytes Retrieved Is Associated with an Increase in 2PNs, Blastocysts, and Cumulative Live Birth Rates.” Fertility and Sterility, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.01.001. Accessed 27 Feb. 2023.

-

Wang, Ange, et al. “Freeze-Only versus Fresh Embryo Transfer in a Multicenter Matched Cohort Study: Contribution of Progesterone and Maternal Age to Success Rates.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 108, no. 2, 1 Aug. 2017, pp. 254-261.e4, www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(17)30363-1/fulltext, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.007.

-

Smith, Andrew D. A. C., et al. “Live-Birth Rate Associated with Repeat in Vitro Fertilization Treatment Cycles.” JAMA, vol. 314, no. 24, 22 Dec. 2015, p. 2654, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.17296.

-

Yanushpolsky, Elena, et al. “Crinone Vaginal Gel Is Equally Effective and Better Tolerated than Intramuscular Progesterone for Luteal Phase Support in in Vitro Fertilization–Embryo Transfer Cycles: A Prospective Randomized Study.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 94, no. 7, Dec. 2010, pp. 2596–2599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.033. Accessed 27 Mar. 2020.

-

Liu, Zheng, et al. “The Impact of Sleep on in Vitro Fertilization Embryo Transfer Outcomes: A Prospective Study.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 119, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2023, pp. 47–55, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0015028222019653, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.10.015. Accessed 7 Jan. 2023.

-

Manheimer, Eric, et al. “Effects of Acupuncture on Rates of Pregnancy and Live Birth among Women Undergoing in Vitro Fertilisation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ, vol. 336, no. 7643, 7 Feb. 2008, pp. 545–549, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39471.430451.be.

-

Lyngsø, Julie, et al. “Impact of Female Daily Coffee Consumption on Successful Fertility Treatment: A Danish Cohort Study.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 112, no. 1, July 2019, pp. 120-129.e2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.03.014.

-

Lyngsø, J, et al. “Low-To-Moderate Alcohol Consumption and Success in Fertility Treatment: A Danish Cohort Study.” Human Reproduction, vol. 34, no. 7, 26 June 2019, pp. 1334–1344, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez050.

-

Li, De-Kun, et al. “Use of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs during Pregnancy and the Risk of Miscarriage.” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, vol. 219, no. 3, 1 Sept. 2018, pp. 275.e1–275.e8, www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(18)30489-7/abstract, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.002. Accessed 16 Aug. 2020.

Share this

Recent Articles

Learn everything you need to know about IVF

Join the newsletter for IVF education, updates on new research, and early access to Alife products.